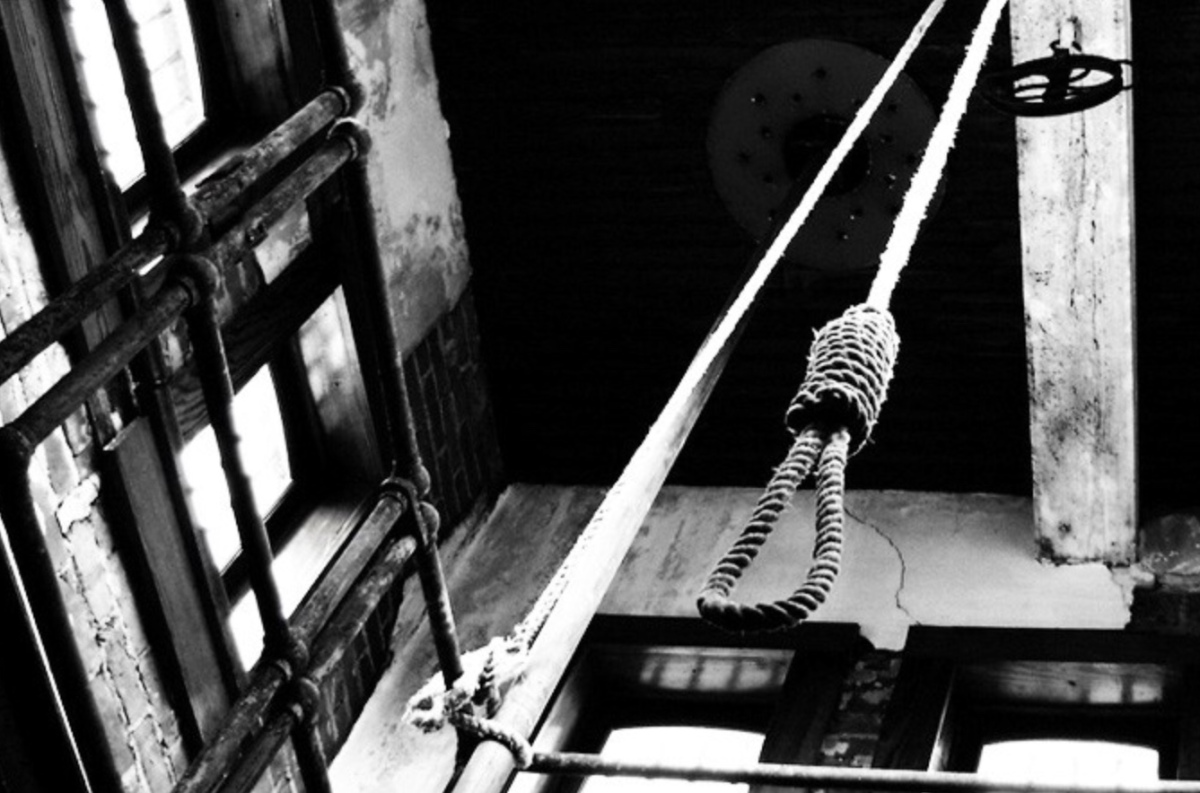

Spotlight regularly features a significant individual or team from the Human Rights community to answer questions put by students from the University of Essex. This month, we focus on an independent advocacy organisation, CAGE. CAGE campaigns against injustice and oppression, and fights on behalf of the victims of human rights violations around the world. The […]